13 Jan Transcending Identities – A Greater Europe

By Laura Petrache and Yannick Le Guern

“The only thing constant is change” We all have heard this phrase. Maybe so much that we tune it out as a “cliché”. The world around us is constantly disrupting us, everywhere in our lives. Surely one will answer: we cannot control what happens to us, but we can control how we respond. But, how do we respond to change, and more importantly how can we influence or even spark it?

As more and more humans cross more and more borders in search of jobs, security and a better future, the need to confront, assimilate or expel strangers, strains political systems and collective identities that were shaped in less fluid times. The European Union was built on the promise to transcend the cultural differences between French, Germans, Spanish and Greeks. It might collapse due to its inability to contain the cultural differences between Europeans and migrants from Africa and the Middle East. But let us not forget that it has been Europe’s very success in building a prosperous multicultural system that drew so many migrants in the first place.

The growing wave of refugees and immigrants produces mixed reactions among Europeans, and sparks bitter discussions about Europe’s identity and future. Some Europeans demand that Europe slam its gates shut. Others call for opening the gates wider… This discussion about immigration often degenerates into a shouting match in which neither side hears the other.

Let us remember that people have always sought the world, have always explored. The Ancient Greek philosopher Diogenes declared, “I am a citizen of the world,” and sought with other cosmopolitans to discern ethical actions for a citizen conscious of what lay beyond the walls, conscious – to do this is still an intellectual problem and paradox for us today – of the unknown, unexplored, or misunderstood. Gandhi advocated for a new social-economic-religious order based on the unity of humanity and the opportunity to be of service. Various traditions speak of right, wrong, fairness, and justice.

Today we have the opportunity to see the overlap and differences among these paths. The assumption that people will live their lives in one place, according to one set of national and cultural norms, in countries with impermeable national borders, no longer holds.

In the 21st century, more and more people will belong to two or more societies at the same time. This is what many researchers refer to as transnational migration. They will claim multiple political and religious identities, to both national and transnational groups. The critical task is to understand the way individuals and organizations actually operate across cultures, and the costs and benefits of these arrangements. It is to understand how ordinary individuals and organizations negotiate these challenges, who wins and who loses, and how they redefine the boundaries of belonging along the way.

Identity, being a person’s sense of self and relation to the world, is understood as dynamic, multiple, diverse and even contradictory.

National identity in Europe has long been rather fluid but over a decade ago the French had a finance minister with the German name Strauss-Kahn, while his German counterpart bore the French name Lafontaine. The 2008 election of Barack Hussein Obama—the son of a Kenyan immigrant with what he cheerfully admitted was a “funny name”, as well as a Muslim one—showed American broad-mindedness at its best. But, America was hardly a global pioneer, Argentina had elected the son of a Syrian immigrant, Carlos Saul Menem, as president, and Peru had done the same with Alberto Fujimori, whose parents were Japanese, though both are overwhelmingly white-majority nations. Mediaeval kings hired their warriors where they could—Indian armies, well before the colonial era, had Turkish artillery gunners, Uzbek horsemen and French generals—and no one found it odd. It is only now that we expect our leaders to conform to a national identity stereotype.

Transcend identities: A matter of belonging, becoming and transcending the boundaries of culture, nationality, class and religion.

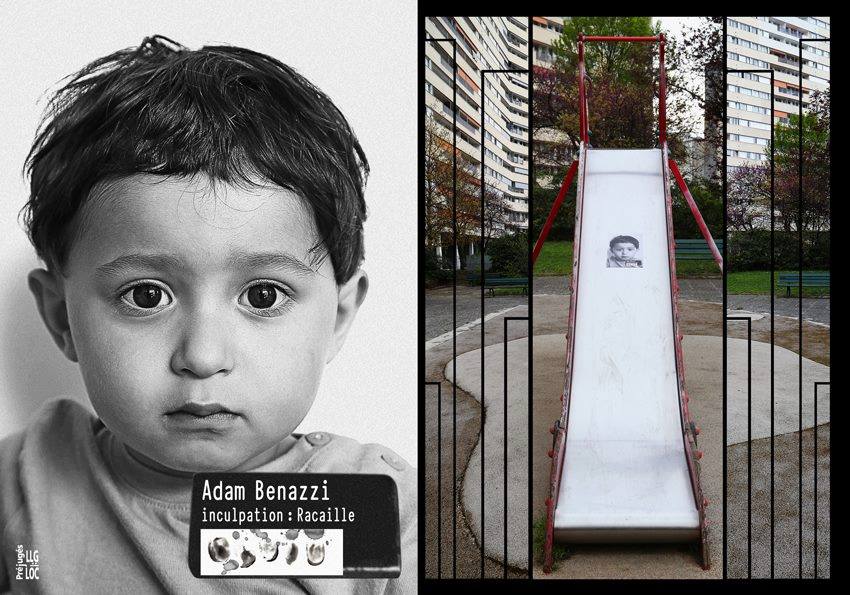

Today we live in a « fractured world” and it is not only visible in world relations but is also continuously increasing, within societies. The rise of populism and protectionism is of concern to those who have relied on closer international cooperation to prosper. Thinking “borders” is not going to help constructing a sustainable future. In today’s world, international migration not only affects those who are on the move but the vast majority of the global population. In today’s uncertain international environment we should seize the opportunity to advance human dignity through a revitalized refugee and migrants response.

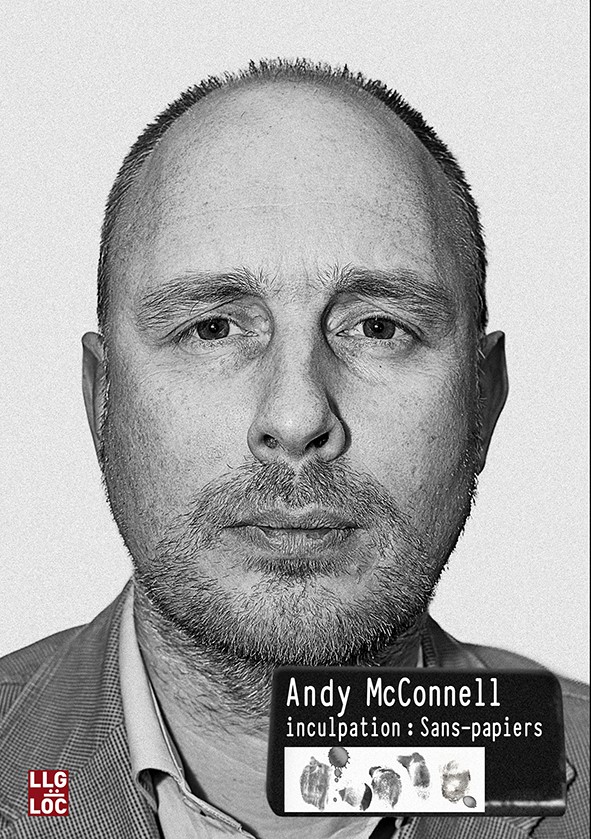

Thinking about borders should be opened up to consider territorial spaces as ‘dwelling’ rather than national spaces and to see political responsibility for pursuit of a ‘decent life’ as extending beyond the borders of any particular state. Borders matter, then, both because they have real effects and because they trap thinking about and acting in the world in territorial terms. A border divides in and out, here and there, self and other. It not only distinguishes, but it separates, actively pushing the sides apart. Border thinking resists the co-presence and connectedness of differentiated and unequal people, whether already inside boundaries (such as immigrants of various statuses) or transnationally.

Rethinking the realities of both migrants and non-migrants in a transnationally connected world could be one solution. In this unprecedented period of migration and forced displacement, people and places are interconnected more than ever before, whether by choice or by necessity. As we know, diversity enriches every society and contributes to social cohesion – something that is all too often taken for granted. Societies with large migrant populations are in many ways trans-local and transnational themselves, already connected to many parts of the world through migrant and diasporic practices and networks.

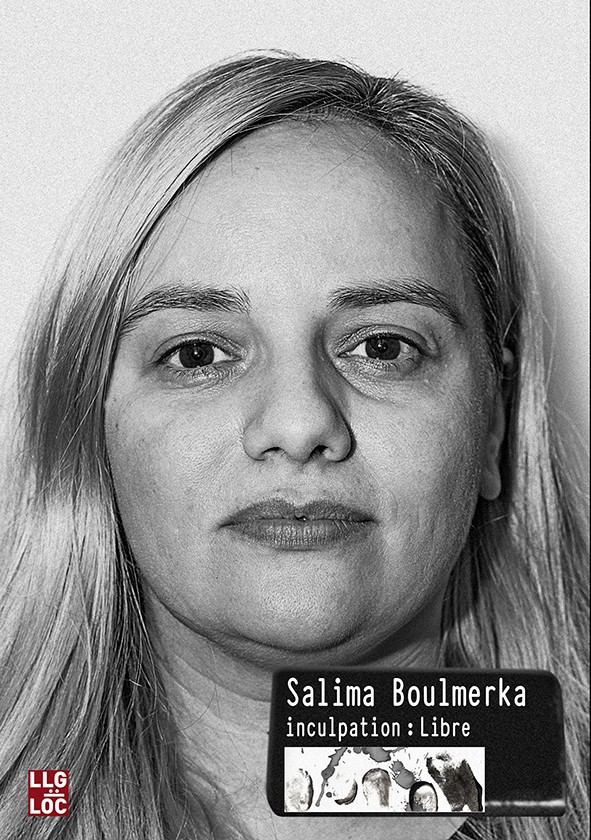

Rethinking migration and migrants from the perspective of movement and not the perspective of the state, would lead to a change; once we accept to operate this change of perspective, we may start to view migrants not as ‘failed citizens,’ but as powerful constitutive (economical, innovating, entrepreneurship and cultural) agents of society’s structure and texture.

How well we integrate migrants and provide opportunities for all members has far reaching implications for and is inextricable from our current and future vitality. Growth, diversity, and dispersion of newcomer populations create opportunities to address longstanding social issues, improve racial and ethnic equity and cohesion, and strengthen our democratic traditions. In terms of the categories of social and individual forms of belonging, transnational citizens are marked by multiple identities and allegiances, and often travel between two or more countries, all in which they have created sizeable networks of differing functions.

Similar to global or cosmopolitan citizenship, it is composed of cross-national and multi-layered memberships to certain societies. Transnational citizenship is based on the idea that a new global framework consistent of subgroups of national identities will eventually replace membership to one sole nation-state. In a hyper-realized version of transnational citizenship, « states become intermediaries between the local and the global. » Institutionalizing transnational citizenship would loosen ties between territories and citizenship and would ultimately result in a reconstruction of world order that forever changes the capacity in which individuals interact with government institutions.

Today’s Europe’s cultural “hybrid identity” can be consider a sustainable key of social development. Trans-nationally, trans-lingually and trans-culturally are the key words for a “sustainable future”; there is no hierarchy amongst and between the cultures we could embrace: they all have their treasures, and can all bring something to a common, positive global project.

New forms of sustainable leadership in a modern era, where fake news spreading like wildfire on social media, are not easy to bear. Key projects like: renewal of European identity, Intergenerational dialogues, sustainable leader’ development and clear communication can be and should be approached through methods of social entrepreneurship and innovation labs. Bringing people into dialogue has to be built on hybrid identities and news ways of exchange. These new ways has to be explored by networks and the invitation on the side of politics to create strong sustainable policies and can create a holistic solution and answer.

Border thinking makes it harder to conceptualize people across boundaries, or migrants who cross them, as moral equals to those within…Today, we stand at a key junction and we can attempt to rectify the world to adhere to closed borders, in a way that damages human lives and recognize that a sustainable world is made out of immigrants and hosts working together towards a shared future: A greater Europe!